How I Spent Seven Years Single-handedly Making a Demonic Thriller – and Accidentally Uncovered My Family’s Dark History

My debut feature Sator (out now on digital) has been the defining project of my life and took me seven years to complete, not least because I made this ever-changing, ever-evolving demonic thriller almost entirely by myself. What started as a simple run-of-the-mill film quickly morphed into something deeply personal, and led me to uncover my family’s dark history.

Back in 2013, after I’d been struggling for some time to raise funds for the film, a friend one day told me out of the blue that he would loan me half my budget in exchange for a percentage. I couldn’t believe it and was almost in tears, knowing I could finally move forward now. So I took the offer, collected my personal savings from wedding videography, and began ordering all the gear I would need to get started.

I shot Sator over 120 days, most days of which consisted of just myself with one or two of the actors. There were about 10 days when I had someone assist me with basic tasks like holding an umbrella when it rained. There was only one day when I had three extra people help me for a couple hours, due to a stunt with fire that would have been too dangerous to do on my own. Out of all of these days, it was Day 10 that changed my world.

When I decided to use my grandmother’s house as a location, I thought it would be pretty neat for her to have a quick one-scene cameo with one my childhood friends, actor Michael Daniel. When we arrived at her house, I set up lights while Michael hid out in the back room. My grandmother was so confused by the lights. “Now what the hell is that contraption?” she would say, and then just laugh. I said she was going to help me with something, but she didn’t care – she just loved the attention. I found Michael in the back room and told him to pretend to be her grandson, and since she’s a very spiritual person, to maybe bring up spirits as well.

Action! Michael comes out and meets her for the first time. “Hi, Nani!” My grandmother is utterly confused, but Michael plays the role of grandson wonderfully. He eventually brings up the spirits, like I asked, then out of nowhere, my grandmother decides to share the voices that used to talk to her through something she called “automatic writing.” What is that? She has never talked to me about that before. Why hasn’t anyone in my family mentioned this before?

After that day, I began doing a little research into my grandmother’s supernatural past. Family members told me vague stories about Ouija boards and seances, but they were all too young at the time to remember all the details. I asked if Nani kept her automatic writings anywhere, and was disappointed to hear she’d burned them all years ago. I knew I had something unique and personal here, though, so I aimed to incorporate as much of it as I could into the story I already had.

I spent a week rewriting the script and editing the footage to make Nani’s scene work. Luckily, there was no schedule on this project, so I had all the time in the world to figure this out. Once the story was solid, I went back to my grandmother and did another improvisational scene. Now, you can’t tell Nani what to say. I tried once: “Hey, Nani. I need you to say, ‘Does Sator love you?’” To which she replied, “Yes, Sator loves me.” You also can never predict anything she says either, so after every day of shooting with her, I would need to take a week-long break to figure out how to make the new footage work for the story. It was a draining process, but that wasn’t even the worst of it.

There are so many stories of the struggle shooting this film, like almost burning down the cabin I built singlehanded for the movie, getting nearly trapped in a snowstorm, the dangers of lighting shit on fire. Or spending thousands of hours (and losing 20 pounds) working on postproduction for the film in my room. For seven years, this one project consumed my life, with little to no change. I cut myself off from everyone and started to wonder if I had just wasted years of my life. But as I love this artform so damn much, it was worth it.

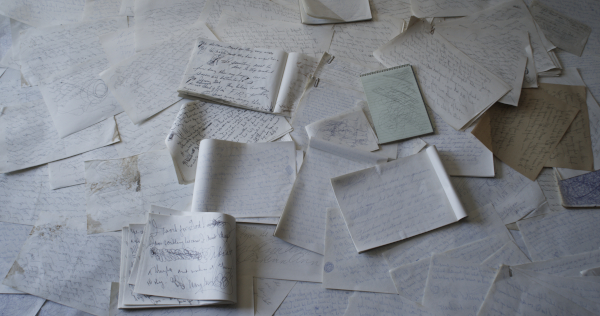

Sometime while I was working on the film’s sound design, Nani’s dementia had made it too dangerous for her to be in her house alone. After she moved into a care home, I helped my family clean out her house. I was going through the closet in the back room when I found two boxes. I opened one box, and there were her automatic writings! Not just a few, but hundreds and hundreds of the ones my family thought she had burned. Looking through them, I was seeing Sator this and Sator that. Before this point, I only knew that Sator was some sort of guardian to my grandmother, nothing more. But then I opened the next box, and inside was a thousand-page journal documenting Nani’s entire journey with Sator and the massive impact he had on her life. Jackpot.

Reading through this journal, I came to learn all about my family’s history with hearing voices. My great-great-grandmother had ended up in a psychiatric hospital because of it. When Nani was just four years old, her mother took her for a drive one stormy night along the coast and aimed the car towards the cliff’s edge, ready to end her suffering. Just as she was about to drive off, she saw her daughter crying in the seat next to her and decided to not kill them both that night. If that had happened, I wouldn’t be writing this. A few months later though, the voices became unbearable for my great-grandmother, and she put a shotgun in her mouth.

In 1968, Nani was in her 40s when she came in possession of a Ouija board and summoned up many beings that only went by initials like FOJ, GEK. AIK, ANN, QXS. QXI was the evil one, the one that would just stand outside your bedroom door at night, watching as you slept. But the leader of them all, and the only one with a real name, was Sator. Nani fell in love with Sator. I literally mean in love, to where she did something called “spiritual lovemaking” with him. I will let your mind wander with that one. Sator also taught her how to move away from the Ouija board and communicate through automatic writing. When all her children went to bed, she would sit in an armchair with a glass of gin, look forward into the void, and let Sator speak through her. Everything he said, she would scribble down. But he wasn’t the only one; the other voices would write through her as well. What gives me goosebumps is that Nani’s handwriting would change with each person, as if that being itself was the one doing the writing. If there was a left-handed spirit, she would write left-handed, and sometimes she would even write backwards. My uncle told me that after he went to bed as a kid, Nani would sit there all night writing and would still be there in the morning when he got ready for school.

The voices in her head eventually got her into trouble, though. She would drive around, having them tell her where to go, but the voices would all argue with each other, causing Nani to get lost. Sator also eventually convinced her that she was the biblical Eve, and after three months of getting into shenanigans with him, she ended up in a psychiatric hospital herself.

Discovering this journal and Nani’s automatic writings was like finding a goldmine. I featured her writings in the opening of the film, where they are spread out for all to see, all things she wrote back in 1968. One day I would love to adapt her full story into a separate film, but at the time of finding these, I was already well into post-production and now desperately trying to find a way to incorporate Sator into the film. It became a race against time to capture Nani speaking about Sator before her dementia completely took over. The first day she talked all about him, but the last day it took 40 minutes of footage to get her to say just three sentences, because he was pretty much wiped from her mind at that point.

This project had so much to do with perfect timing. If I had waited any longer to make it, I wouldn’t have been able to capture what I did with my grandmother. Also, the time I spent getting to know her and being able to immortalize her in this film was invaluable to me. She and I really bonded over this whole experience. She’d call me every day saying, “Hey, when are you going to come over and spend some time with me?” Unfortunately, she passed before I finished the film, but she did see one clip of herself. Her only comment was, “Who’s that old goat?”

But I did finally finish the film! I didn’t have any doubt about that, actually; I just wasn’t expecting it to take so long. Sator got accepted into Fantasia International Film Festival and a handful of other festivals, and what a rollercoaster of emotions that has been! Being isolated for so long and then being thrown into crowds of people was not an easy transition for me, but it was really worth it in the end. It was an amazing experience to travel the world and talk to so many fascinating people whom the film resonated with. To everyone who has approached me, I really do appreciate the conversations we have had.

Looking back, I wouldn’t recommend making a feature film by yourself, and will never do that again. But I value what the experience has taught me and have grown a lot as a filmmaker. Hopefully, I have done enough to prove my worth with Sator and will inspire some people out there to want to work with me on future projects. Or at least help me set up the tripod.